Learning how SARS-CoV-2 highjacks host cell machineries will help to develop therapeutic strategies

As the global coronavirus pandemic continues, scientists are not only trying to find vaccines and drugs to combat it, but also to continuously learn more about the virus itself. “By now we can expect the coronavirus to become seasonal,” explains Ralf Bartenschlager, professor in the Department of Infectious Diseases, Molecular Virology, at Heidelberg University. “Thus, there is an urgent need to develop and implement both prophylactic and therapeutic strategies against this virus.” In a new study, Bartenschlager, assisted by the Schwab team at EMBL Heidelberg and using EMBL’s Electron Microscopy Core Facility, performed a detailed imaging analysis to determine how the virus reprograms infected cells.

Cells that become infected by SARS-CoV-2 die rather quickly, within only 24 to 48 hours. This indicates that the virus harms the human cell in such a way that it is rewired and essentially forced to produce viral progeny. The main aim of the project was therefore to identify the morphological changes within a cell that are inherent to this reprogramming. “To develop drugs which suppress the viral replication and thereby the consequence of the infection, as well as the virus-induced cell death, is key to have a better understanding of the biological mechanisms driving the virus’ replication cycle,” explains Bartenschlager. The team used the imaging facilities at EMBL and state-of-the art imaging techniques to determine the 3D architecture of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells, as well as alterations of cellular architecture caused by the virus.

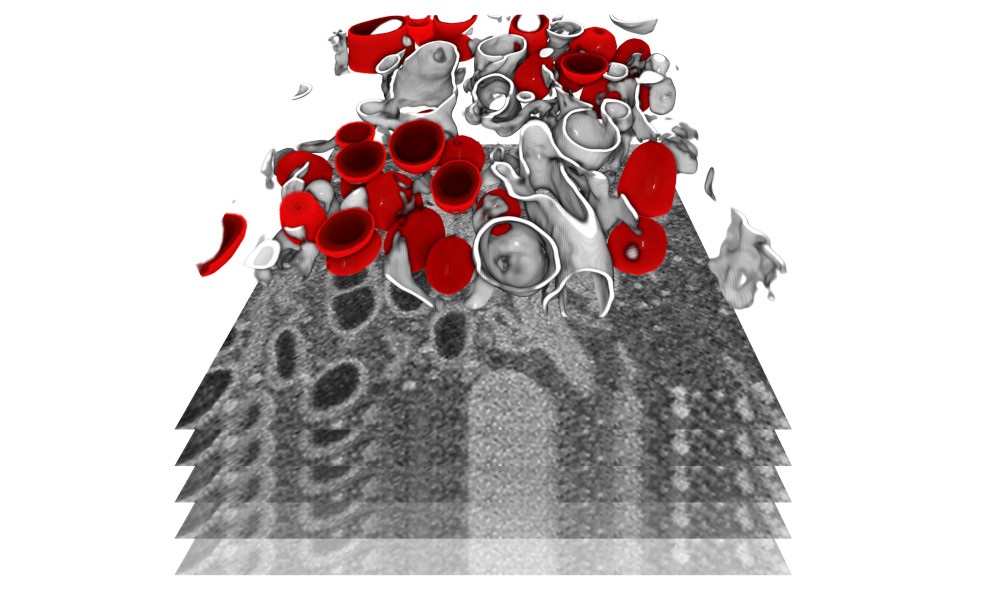

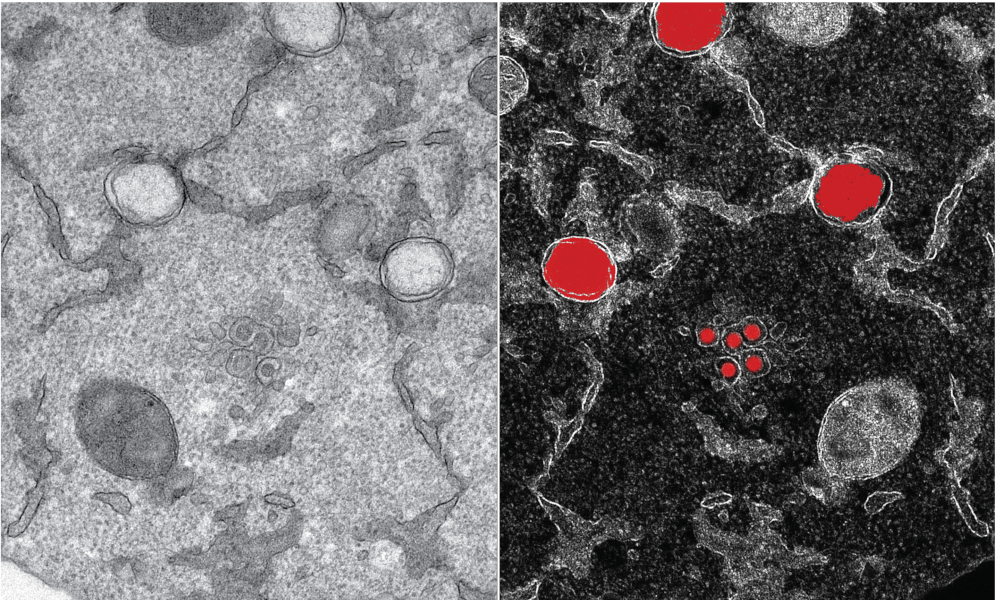

The team was able to create 3D reconstructions of whole cells and their subcellular compartments. “We are providing critical insights into virus-induced structural changes in the studied human cells,” explains Ralf Bartenschlager. The images revealed an obvious and massive change in the endomembrane systems of the infected cells – a system that enables the cell to define different compartments and sites. The virus induces membrane changes in such a way that it can produce its own replication organelles. These are mini replication compartments where the viral genome is amplified enormously. To do this, the virus requires membrane surfaces. These are created by exploiting a cellular membrane system and creating an organelle, which has a very distinct appearance. The scientists describe it as a massive accumulation of bubbles: two membrane layers forming a big balloon. Within these balloons – which form a very shielded compartment – the viral genomes are multiplied and released to become incorporated into new virus particles.

This striking change can be seen in the cells only a few hours after infection. “We saw how and where the virus replicates within the cell, and how it hijacks its host machinery to be released after multiplication,” Schwab says. Until now, little was known about the origin and development of the effects that SARS-CoV-2 causes in the human body. This includes a lack of knowledge about the mechanism by which the infection leads to the death of infected cells. Having this information now will foster the development of therapies reducing virus replication and, thus, disease severity.

The team has made sure that the collected information and, in particular, the unprecedented repository of 3D structural information about virus-induced substructures can be used by everyone. “I believe we are setting a precedent on the fact that we are sharing all data that we produced with the scientific community. It represents an impressive resource to the community,” says Yannick Schwab. “This way we can support the global effort to study how SARS-CoV-2 interacts with its host.” The team hopes that their collected information will help in the development of antiviral drugs.

The team managed to produce the study in an incredibly short time, despite the challenging circumstances.

“Half the world – and of course Heidelberg as well – were in full lockdown and we had to improvise almost on a daily basis to adapt to the situation. Whether at EMBL or from home, all were deeply involved and generously gave their time and deep knowledge,” says Schwab. “The speed at which we worked, and the amount of data that was produced, is remarkable.”

This article is also available in German

This article was originally published on EMBL News